Plastic pollution is everywhere.

Each year over 368 million tonnes of plastics are produced with over 13 million tonnes of it ending up in the soil where it can be toxic to wildlife.

Our research team is particularly worried about the environmental impacts of ‘microplastics’ which are small plastic particles less than 5 mm in size.

Microplastics can be produced from products like glitter or when larger objects including water bottles break down into smaller and smaller pieces once they’re in the environment.

Due to their small size, animals can eat microplastics mistaking them for food which can cause starvation and malnutrition as well as abrasions to gastrointestinal tracts.

A lot of research has shown microplastics are toxic to ocean species but far fewer studies have investigated the impacts of microplastics on land-dwelling species. This is despite annual plastic release onto the land being estimated at over four times the level that enters the oceans.

Glitter is a type of microplastic used in cosmetics, clothing or for decorative purposes.

Most glitter is made of a plastic called polyethylene terephthalate which you probably know as PET. It’s the same plastic that is used for bottled water and soft drink containers.

Conventional glitter also often contains aluminium or other metals which is where the sparkle comes from.

We don’t know much yet about how much glitter is getting into the environment but anyone who has ever worn glitter make-up or used glitter in art and craft knows it seems to end up everywhere.

In 2023, the European Union officially banned the sale of loose plastic glitter and some other products that contain microbeads, in a bid to cut environmentally harmful microplastic pollution in member nations by 30 per cent by 2030.

So far, Australia has not followed suit.

One study in New South Wales, Australia, found that 24 per cent of the microplastics in sewage sludge were glitter.

Once glitter gets into the environment it is difficult to remove because of its tiny size and because it can become transparent over time on losing the metal components.

While biodegradable glitter is already commercially available, previous research indicates these products could be just as harmful or even more toxic to aquatic organisms than conventional PET glitter because most biodegradable varieties on the market need to be coated in a coloured aluminium layer and topped with a thin plastic layer.

So part of our research team, based at the University of Cambridge, has been working on making more sustainable glitter.

They have created a novel nanocrystal made from cellulose that sparkles in light and is biodegradable. Cellulose is made from glucose and is the component that gives tree wood its strength.

We wanted to compare the potential toxicity of conventional glitter with the new cellulose glitter as part of testing how sustainable the new glitter is. The study is now published in the journal Chemosphere.

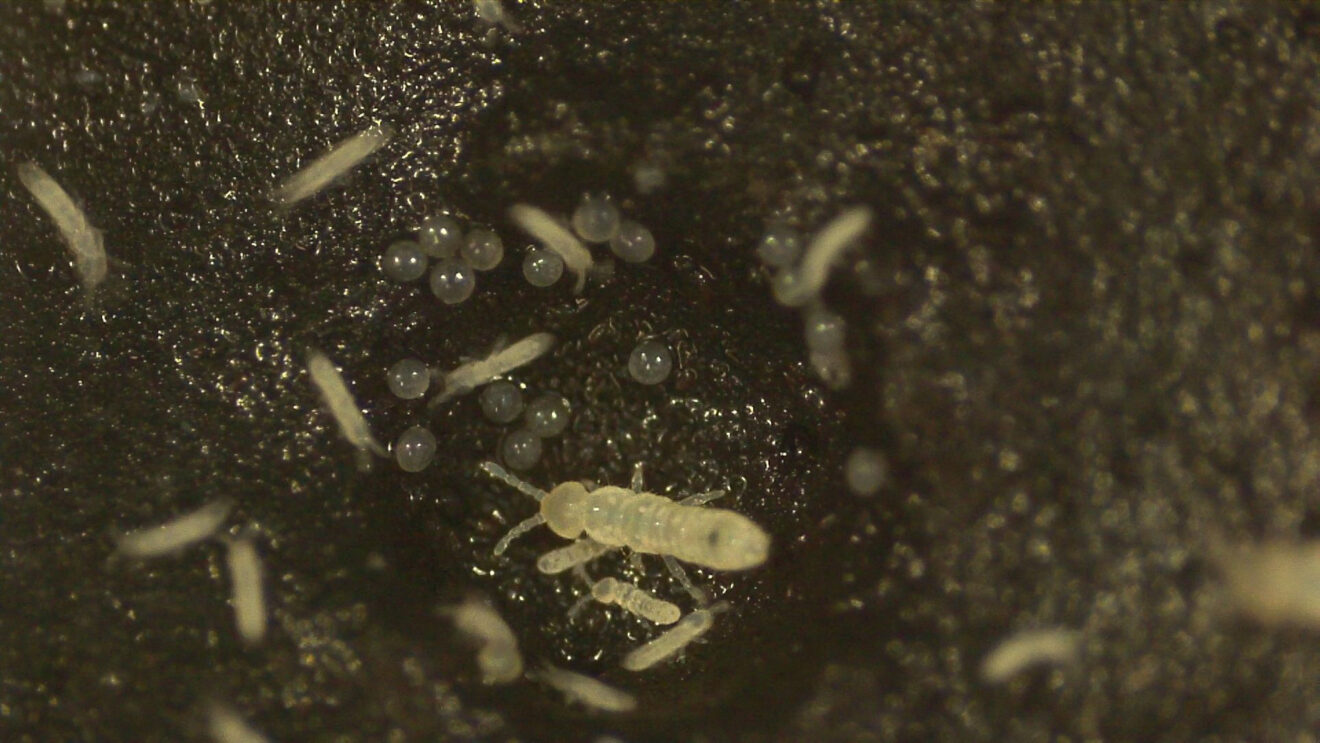

We used a little soil critter called a springtail (Folsomia candida) for our research. Springtails are small, white, eyeless invertebrates that are closely related to insects. They are widespread in soils around the world where they feed on leaf litter and compost.

These critters are used as an indicator of soil quality and because they are sensitive to toxic compounds, are often used to test for potential pollutants.

Using soil from the University of Melbourne’s Dookie campus, we exposed the springtails to different concentrations of conventional and cellulose glitter and studied the impact on their reproduction, survival and growth.

We found that neither glitter impacted springtail survival or size. However, once the concentrations of conventional glitter in the soil reached 1000 mg of glitter per kg of soil the reproduction of the springtails was reduced by 61 per cent.

The level of contamination we studied is on par with a soil contaminated with microplastics. Contaminated soils have been found to have up to approximately 100,000 mg per kg of microplastics with most soils below 10,000 mg per kg.

In comparison to conventional glitter, there were no toxic effects on springtail reproduction at any concentration of the cellulose glitter.

So although it’s promising that neither type of glitter was directly harmful to the springtails, it’s worrying that the conventional glitter affected their ability to reproduce.

Fewer springtails being born can weaken their population, which might lead to bigger problems for soil health like less organic matter breaking down and fewer nutrients being released for plants.

So we suggest you think twice before using conventional glitter in make-up, clothing or for arts and crafts but are hopeful that you’ll soon be able to buy a safer, more sustainable and just as sparkly alternative.

The study research team included Po-Hao Chen, Suzie Reichman, Ian Lam and Zhuyun Gu, University of Melbourne; Silvia Vignolini, Benjamin E. Droguet, University of Cambridge; Dannielle Green, Anglia Ruskin University and Shamali De Silva, Environment Protection Authority Victoria