If you search Google Scholar for the phrase “as an AI language model”, you’ll find plenty of AI research literature and also some rather suspicious results. For example, one paper on agricultural technology says:

As an AI language model, I don’t have direct access to current research articles or studies. However, I can provide you with an overview of some recent trends and advancements …

Obvious gaffes like this aren’t the only signs that researchers are increasingly turning to generative AI tools when writing up their research. A recent study examined the frequency of certain words in academic writing (such as “commendable”, “meticulously” and “intricate”), and found they became far more common after the launch of ChatGPT – so much so that 1% of all journal articles published in 2023 may have contained AI-generated text.

(Why do AI models overuse these words? There is speculation it’s because they are more common in English as spoken in Nigeria, where key elements of model training often occur.)

The aforementioned study also looks at preliminary data from 2024, which indicates that AI writing assistance is only becoming more common. Is this a crisis for modern scholarship, or a boon for academic productivity?

Many people are worried by the use of AI in academic papers. Indeed, the practice has been described as “contaminating” scholarly literature.

Some argue that using AI output amounts to plagiarism. If your ideas are copy-pasted from ChatGPT, it is questionable whether you really deserve credit for them.

But there are important differences between “plagiarising” text authored by humans and text authored by AI. Those who plagiarise humans’ work receive credit for ideas that ought to have gone to the original author.

By contrast, it is debatable whether AI systems like ChatGPT can have ideas, let alone deserve credit for them. An AI tool is more like your phone’s autocomplete function than a human researcher.

Another worry is that AI outputs might be biased in ways that could seep into the scholarly record. Infamously, older language models tended to portray people who are female, black and/or gay in distinctly unflattering ways, compared with people who are male, white and/or straight.

This kind of bias is less pronounced in the current version of ChatGPT.

However, other studies have found a different kind of bias in ChatGPT and other large language models: a tendency to reflect a left-liberal political ideology.

Any such bias could subtly distort scholarly writing produced using these tools.

The most serious worry relates to a well-known limitation of generative AI systems: that they often make serious mistakes.

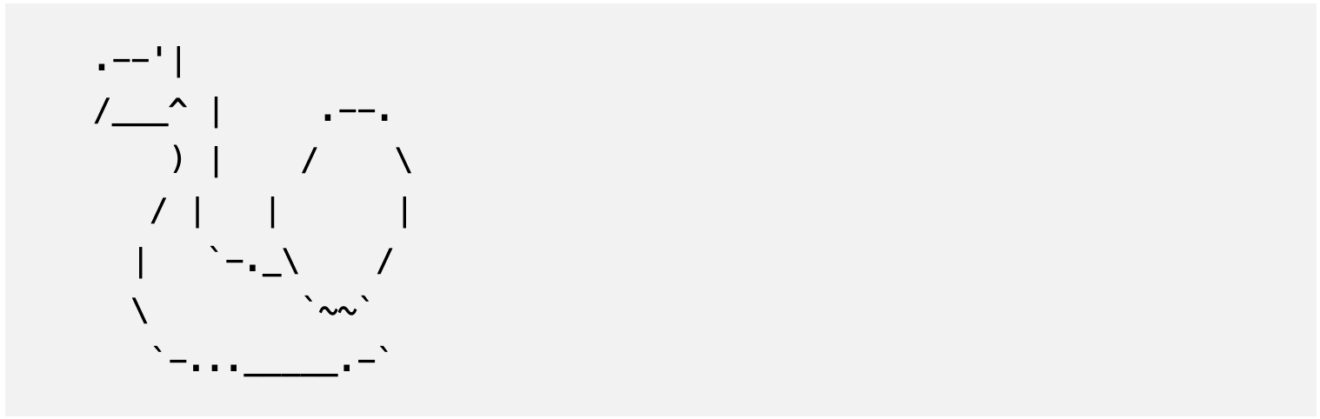

For example, when I asked ChatGPT-4 to generate an ASCII image of a mushroom, it provided me with the following output.

It then confidently told me I could use this image of a “mushroom” for my own purposes.

These kinds of overconfident mistakes have been referred to as “AI hallucinations” and “AI bullshit”. While it is easy to spot that the above ASCII image looks nothing like a mushroom (and quite a bit like a snail), it may be much harder to identify any mistakes ChatGPT makes when surveying scientific literature or describing the state of a philosophical debate.

Unlike (most) humans, AI systems are fundamentally unconcerned with the truth of what they say. If used carelessly, their hallucinations could corrupt the scholarly record.

One response to the rise of text generators has been to ban them outright. For example, Science – one of the world’s most influential academic journals – disallows any use of AI-generated text.

I see two problems with this approach.

The first problem is a practical one: current tools for detecting AI-generated text are highly unreliable. This includes the detector created by ChatGPT’s own developers, which was taken offline after it was found to have only a 26% accuracy rate (and a 9% false positive rate). Humans also make mistakes when assessing whether something was written by AI.

It is also possible to circumvent AI text detectors. Online communities are actively exploring how to prompt ChatGPT in ways that allow the user to evade detection. Human users can also superficially rewrite AI outputs, effectively scrubbing away the traces of AI (like its overuse of the words “commendable”, “meticulously” and “intricate”).

The second problem is that banning generative AI outright prevents us from realising these technologies’ benefits. Used well, generative AI can boost academic productivity by streamlining the writing process. In this way, it could help further human knowledge. Ideally, we should try to reap these benefits while avoiding the problems.

The most serious problem with AI is the risk of introducing unnoticed errors, leading to sloppy scholarship. Instead of banning AI, we should try to ensure that mistaken, implausible or biased claims cannot make it onto the academic record.

After all, humans can also produce writing with serious errors, and mechanisms such as peer review often fail to prevent its publication.

We need to get better at ensuring academic papers are free from serious mistakes, regardless of whether these mistakes are caused by careless use of AI or sloppy human scholarship. Not only is this more achievable than policing AI usage, it will improve the standards of academic research as a whole.

This would be (as ChatGPT might say) a commendable and meticulously intricate solution.