Dr Richard Gillespie's personal history is closely intertwined with The University of Melbourne. Dr Gillespie studied and taught at the University before plying his trade in the world of museums. It's only fitting then, that after 25 years the University again came calling for Dr Gillespie.

Now the curator for the Engineering and Information Technology Collection, Richard's historical knowledge of the faculty is second to none. We sat down with Richard to hear about how the University's Museums and Collections department works, and how we're celebrating the University's rich engineering and IT history everyday through the work showcased at Melbourne Connect.

Hi Richard, thanks for taking the time to speak with us. Can you please tell us about your role at the University?

I'm Richard Gillespie, curator of the Engineering and Information Technology (IT) Collections here at the University. I look after all the historical artefacts and the history of the buildings that the Engineering and IT Faculty sits in.

What background have you come from to take on this role?

I trained as an historian of science here at The University of Melbourne. Then I studied overseas before returning as a lecturer in the history of science. I then got tempted into the museum world and for 25 years I worked at Museums Victoria, developing Science Works, the Immigration Museum, Melbourne Museum, and becoming a manager within the Museums Victoria team. The last few years I've come back to a more curatorial and more hands on role, which has been fantastic.

What drew you back into that curatorial role as opposed to staying with Museums Victoria?

The role I had at the museum got split up, so it was a good time for me to depart and do something new. I started working here at the University on the Computing and Information Systems collection. That role then gradually expanded to be looking across the whole faculty of work for Engineering and Information Technology.

Can you explain to us what the Museums and Collections department does within the University?

There are about 35 collections across the University that are sitting within the different faculties. The medical faculty has three separate collections, architecture has one, there are the rare books and archives, as well as the art collections in the different galleries. The Grainger Museum is something people will know as well.

Many of these are managed within faculties., though the University Museums and Collections Department was set up several years ago to allow some sort of overarching control of the collections and the Grainger collection. They also play a strategic role in helping coordinate and identify any potential issues and larger planning for all 35 collections.

How many people make up that museum collections team?

There are around 40 people working within Museums and Collections. Then, of course, there's the staff working on collections in all the other faculties and areas of the University. Some of those are full time and some people tack these roles onto their existing roles.

Tell us a bit about the collection within the Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology.

The formal Engineering and IT collection was only formed about four years ago, and that was really triggered by me coming in and taking an overarching perspective on the whole collection.

The collections of separate departments had been managed or established by staff going back to the 1940s and 50s. They became sort of Cinderella collections in that the person responsible retired and then there was nobody to take up the baton. So there were several collections within the faculty, some very well managed and maintained with a database on the computing collection. Other collections had become sort of widowed collections, or as we call them, Cinderella collections.

What portion of the Engineering and IT collection are we seeing on display here at Melbourne Connect at any one time?

There's probably about 1400 objects in the Engineering and IT collection. That's grown substantially in the last few years as I've been able to identify a lot of material that's sitting in laboratories that has historical significance, things that have never been documented. So about 1400 objects, 2500 photographs and some archival records as well.

In Melbourne Connect and the other engineering buildings on the Parkville campus, it's probably about 12% of the collection that is on display. That seems small, relatively speaking, but if you ask most museums, they'll say it's a 0.01% of their collection on display at any time. The collection is now online as well, so there's different ways in which the collection can be accessed rather than just the displays.

What's the importance of this collection to the University?

If you think about students coming to the university, they're here for three, four, five years, staff equally actually have quite a substantial turnover. So people are coming in and then departing again. I think of the collections as being a way of holding that history and that tradition so that when new students or staff arrive, they feel that they're part of something that has the kind of depth that the University of Melbourne has. We have collections going back right to the start of the engineering course in 1861. We want to make it possible to connect to that tradition.

I’d love to dive into the story of a few pieces within the collection itself. Can you tell us a bit about the importance of the Munnari computer?

The Munnari computer was the mini computer in the computer science department in the 1970s and early 80s. It really supported the research project within the department and also the student teaching as well. The Department of Meteorology used it for a lot of meteorological data crunching on climate and early research on climate change. Though it is best known because it became the node for Australia's first connection to the internet in 1989.

What is the significance behind the name of that computer?

When the computer science technicians wanted to name the computers, they had the brainwave of saying, why don't we choose words starting with a MU for Melbourne University to name the computers. They got an Aboriginal dictionary and then applied words starting with MU from that Aboriginal dictionary. They did so without any kind of consultation with the traditional owners of those languages.

We decided about four years ago that we should reach out to the traditional owners and we identified that the name had originally come from the Ngarrindjeri community in the south east of South Australia. We wrote to them and explained the situation, that they hadn't been in consultation at the time and that we would like to rectify that. They discussed it with the Traditional Owners Council and agreed that we could continue to use the name, and we found a way of acknowledging the role of that computer by naming the Manhari room up on level seven of Melbourne Connect. They asked that we use the current orthography, the current spelling, which is Manhari rather than Munnari. So a slight difference in pronunciation.

Can you talk to us about the pieces of the collection from the Budj Bim cultural landscape and the relationship between the University and the Gunditjmara Traditional Owners?

The University has been working for several years with the Gunditjmara Traditional Owners cooperation to document the cultural landscape at Budj Bim. This includes 6000 years of aquaculture systems that used the lava flows and channels for catching eel. That's been a project that's been going for several years and we wanted to celebrate and acknowledge that partnership here in Melbourne Connect.

There are no objects, per se, as you can't really bring parts of the lava channels into a showcase. So we commissioned, with Sandra Aitken, who's a weaver and artist, to make an eel trap for us that we could display. I know Sandra has subsequently made a larger one as well for the Museums and Collections department that will be displayed at the Potter Gallery.

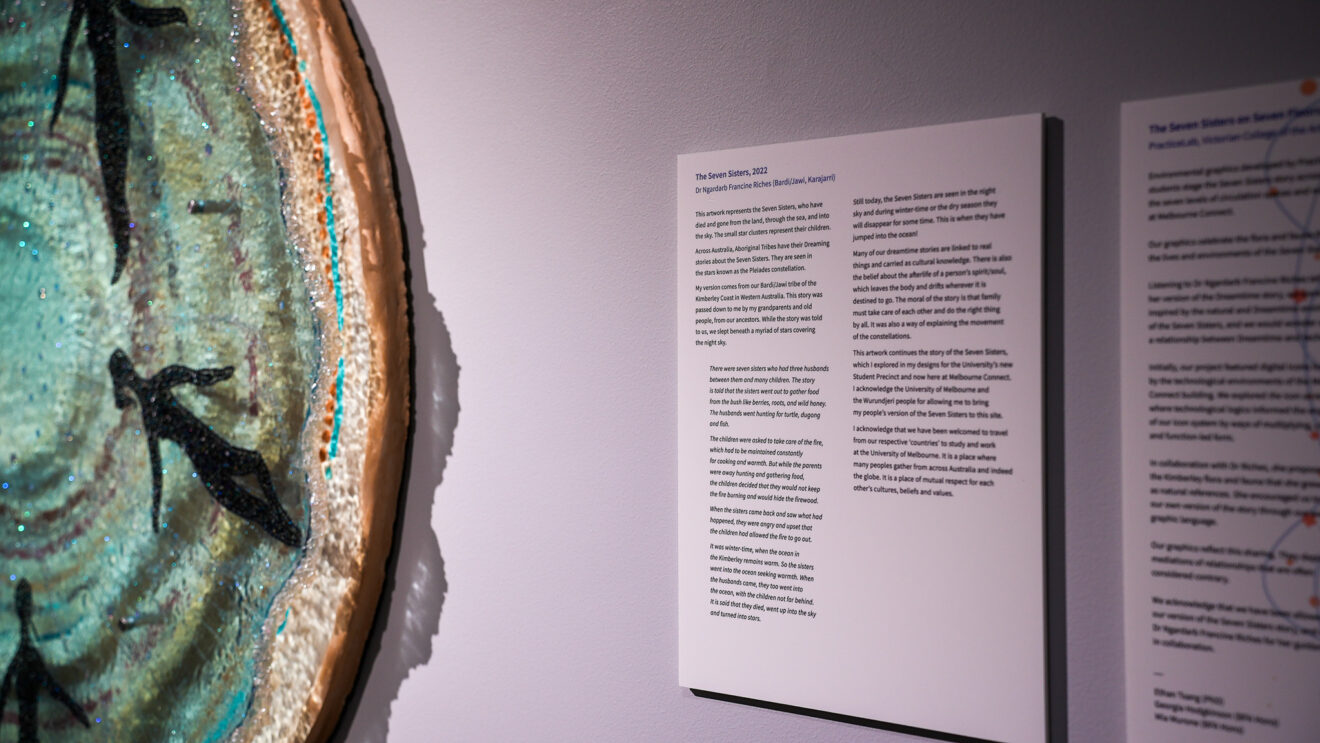

The Seven Sisters artwork sits outside the Manhari room on level 7, how has that artwork has been weaved through the floors of Melbourne Connect?

We wanted to represent and celebrate indigenous knowledge systems within the Engineering and IT spaces at Melbourne Connect, so we reached out to the Victorian College of the Arts and to the Wilin Centre and they recommended somebody we could work with, an artist by the name of Ngardarb Francine Riches. Ngardarb had worked on the student precinct as well, telling aspects of the story of the Seven Sisters. Her version of it comes from the Bardi/Jawi community in the Kimberley.

After talking with Ngardarb we then commissioned her to create a sculpture, essentially an artwork, that would celebrate the story of the Seven Sisters. The artwork focuses on the relationship both to the constellation of the Pleiades, but also the stories that she had learned from her grandparents as a young child lying and looking at the stars in the Kimberley.

Ngardarb created a beautiful artwork that reflects the Seven Sisters going into the ocean, as they do each year when the constellation of the sinks below the horizon. We then wanted to also bring that artwork into the corridors and the office areas at Melbourne Connect. We worked with students from the Victorian College of the Arts to take the story of the Seven Sisters and translate that into a series of graphics that we could then apply throughout the seven floors of Melbourne Connect. It's a very beautiful result.

What are some of your favourite pieces in the collection particularly and why?

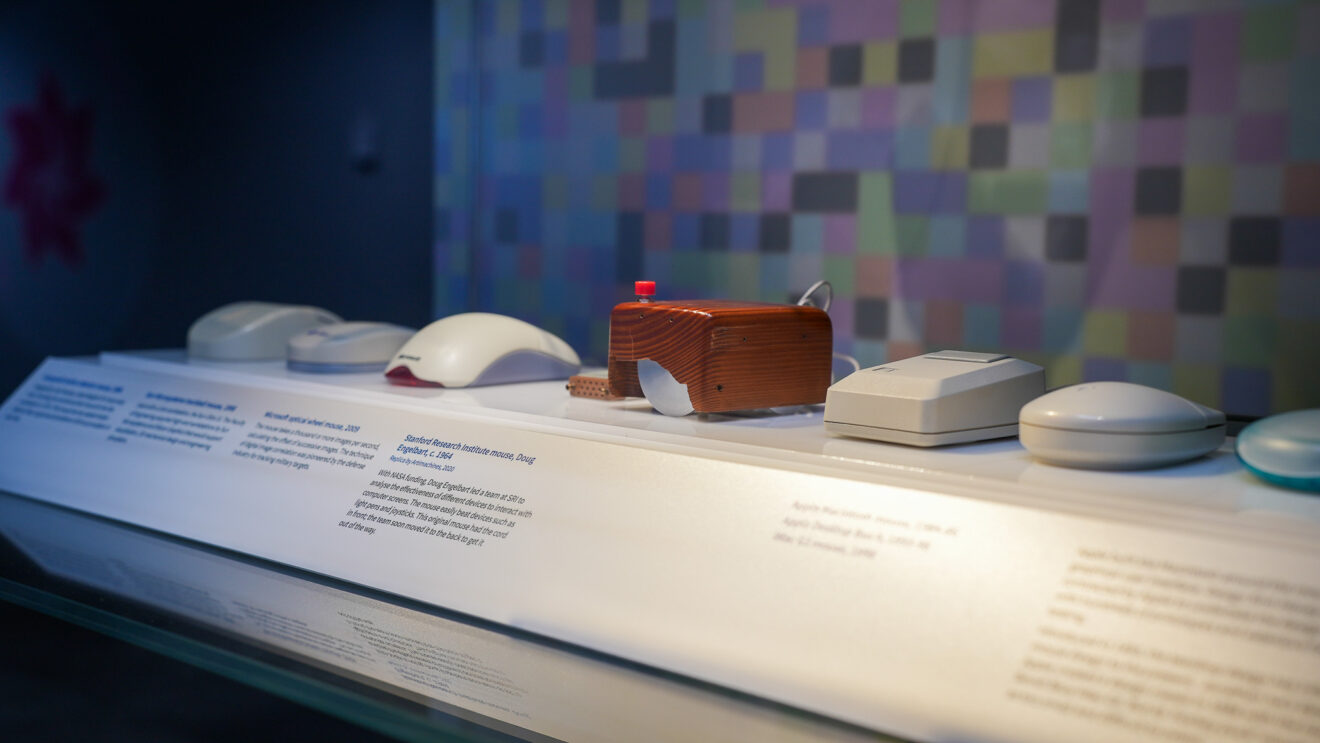

Usually the last object I'm working on is my temporary favourite, until I discover a new one that I want to explore. One of my favourite objects is the control console of the IBM 7044 computer. The 1964 mainframe computer, which was the second computer acquired by the University and really transformative in that a much larger number of researchers and staff could access computing power. It's a beautiful object, 1960s design, very IBM, very redolent of the space age. Having that on display and next to it the memory component, which is the size of a small bar fridge and it's all of 32kB. It’s just an extraordinary artefact.

What do you enjoy about being able to work in this precinct?

The great thing about Melbourne Connect is that it's just bringing so many different people together with different skill sets, different perspectives. One of the things I've been trying to do is start talking to some of the co-located partners and companies based at Melbourne Connect, and some of those companies have actually emerged from research done within the University. I've started talking to them about ways we can showcase their work as well. So it's not just about the Engineering and IT collection, but it's actually celebrating the work that's done here as a whole.

Of course there's a limit to what you can collect and what you can fit into a showcase. The area that I have really struggled to find ways of telling current research and stories is in nanotechnology and some of the biomedical engineering research. It is possible to kind of tell those stories, such as the cochlear implant and bionic ear, for example. But in terms of doing nanotechnology and chemical engineering and biomedical engineering, it's rather challenging. At the other end of the scale, the kind of research that's been done on wild storms and oceans and so forth in Antarctica, you know, how do you capture that? There's always a limit to what I can do, but it doesn't stop me thinking about ways in which there might be a way to represent those stories.

How do you feel about the future of collections with the influence of artificial intelligence?

I think the future opens up all kinds of new possibilities in terms of new technologies, AI, and digitisation that we can apply to collections. One of the aspirations of the University is that every student, through their time at the University, will have some exposure and some interaction with collections. So we are now working to think about how we can achieve that. How can we create a discovery portal and digitised collections, 3D versions of objects so that they can be manipulated virtually by students and then integrated into the learning management system? The potential for AI to analyse those objects or to reconstruct objects in different ways is just very exciting.

Thanks very much for your time, Richard, we look forward to seeing more pieces of the collection on display over the coming months.